Chapter 1 Case Study

In this chapter, first, we describe the aim of the study. Subsequently, we describe the sample included in the study. We present general information about the sample and the results of the cluster analysis to classify the different attachment patterns. Finally, we consider children’s social-emotional problems.

1.1 Aim of the Study

The study aims to compare the different theoretical perspectives regarding the role of mother attachment and father attachment on children’s social-emotional development. In the literature, four different main theoretical perspectives have been identified (Bretherton, 2010):

- Monotropy Theory - only the mother has an impact on children’s development.

- Hierarchy Theory - the mother has a greater impact on children’s development than the father.

- Independence Theory - all attachment figures are equally important but they affect the children’s development differently.

- Integration Theory - to understand the impact on children’s development it is necessary to consider attachment relationships taken together.

Contrasting results have been reported by studies investigating which is the “correct” theory. No study, however, has tried to properly evaluate the different theoretical perspectives by directly comparing the different hypotheses.

For more information regarding Attachment theory and the formalization of theoretical perspectives regarding the role of mother attachment and father attachment on children’s socio-emotional development, see the main article available at https://psyarxiv.com/6kc5u.

1.2 The Study Sample

To evaluate the different roles of father attachment and mother attachment, we consider 854 Italian children from third to sixth school grade. Only middle-childhood children are included in the analysis (5 participants are excluded as older than 12.3 years and 2 participants are excluded as the age is missing). The total sample size included in the analysis is 847 (50.65 % Females). Participants’ frequencies by grade and gender are reported in Table~1.1.

| Grade | Females | Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd | 133 | 127 | 260 |

| 4th | 81 | 75 | 156 |

| 5th | 36 | 32 | 68 |

| 6th | 179 | 184 | 363 |

| Total | 429 | 418 | 847 |

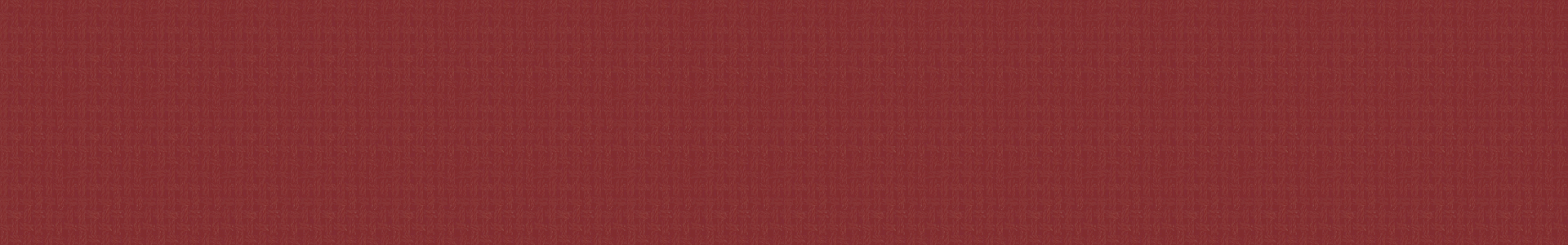

Participants’ age mean is 10.28 (SD = 1.34). The participants’ age summary statistics are reported below and the distribution is presented in Figure~1.1.

## # Age summary statistics

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 7.92 9.00 10.25 10.28 11.58 12.25

Figure 1.1: Participants age distribution (\(n_{subj} = 847\))

1.3 Attachment Styles

Attachment towards the mother and the father was measured separately using the brief Experiences in Close Relationships Scale - Revised Child Version (ECR-RC, Brenning et al., 2014; Marci et al., 2019) completed by the children. Four main attachment styles have been recognized in the literature according to thee levels of anxiety and avoidance:

- Secure Attachment - children with low levels of anxiety and avoidance.

- Anxious Attachment - children characterized by high levels of anxiety.

- Avoidant Attachment - children characterized by high levels of avoidance.

- Fearful Attachment - children with high levels of anxiety and avoidance.

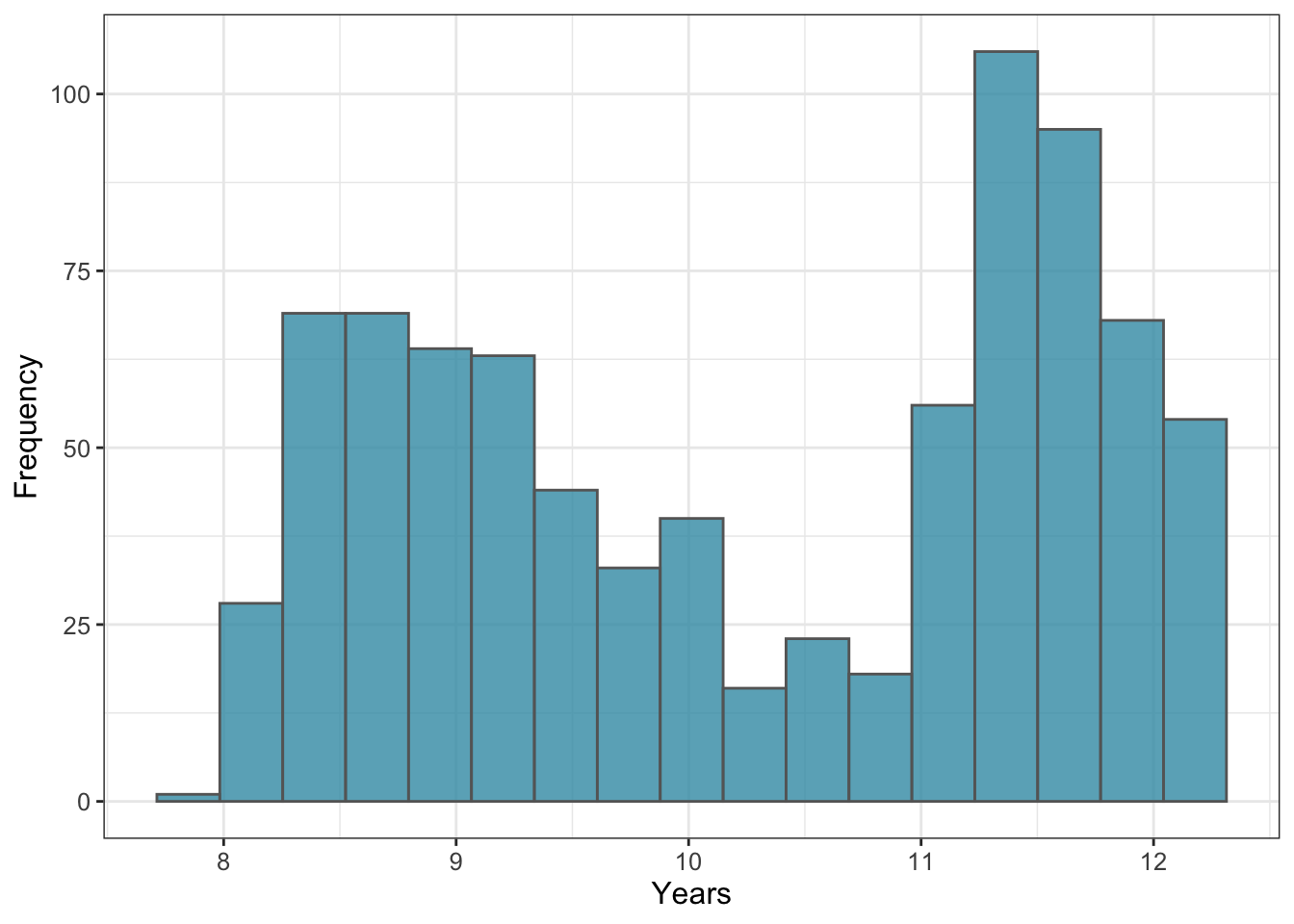

To identify children’s attachment styles towards the mother and towards the father, we conduct two separate cluster analyses. Clusters are obtained using the function hclust() (with argument method="ward.D") considering Euclidean distances between participants responses to the ECR items.

1.3.1 Mother Cluster Analysis

Regarding mother attachment, 4 groups are selected from the cluster analysis results (see Figure~1.2).

Figure 1.2: Mother attachment cluster dendrogram (\(n_{subj} = 847\)).

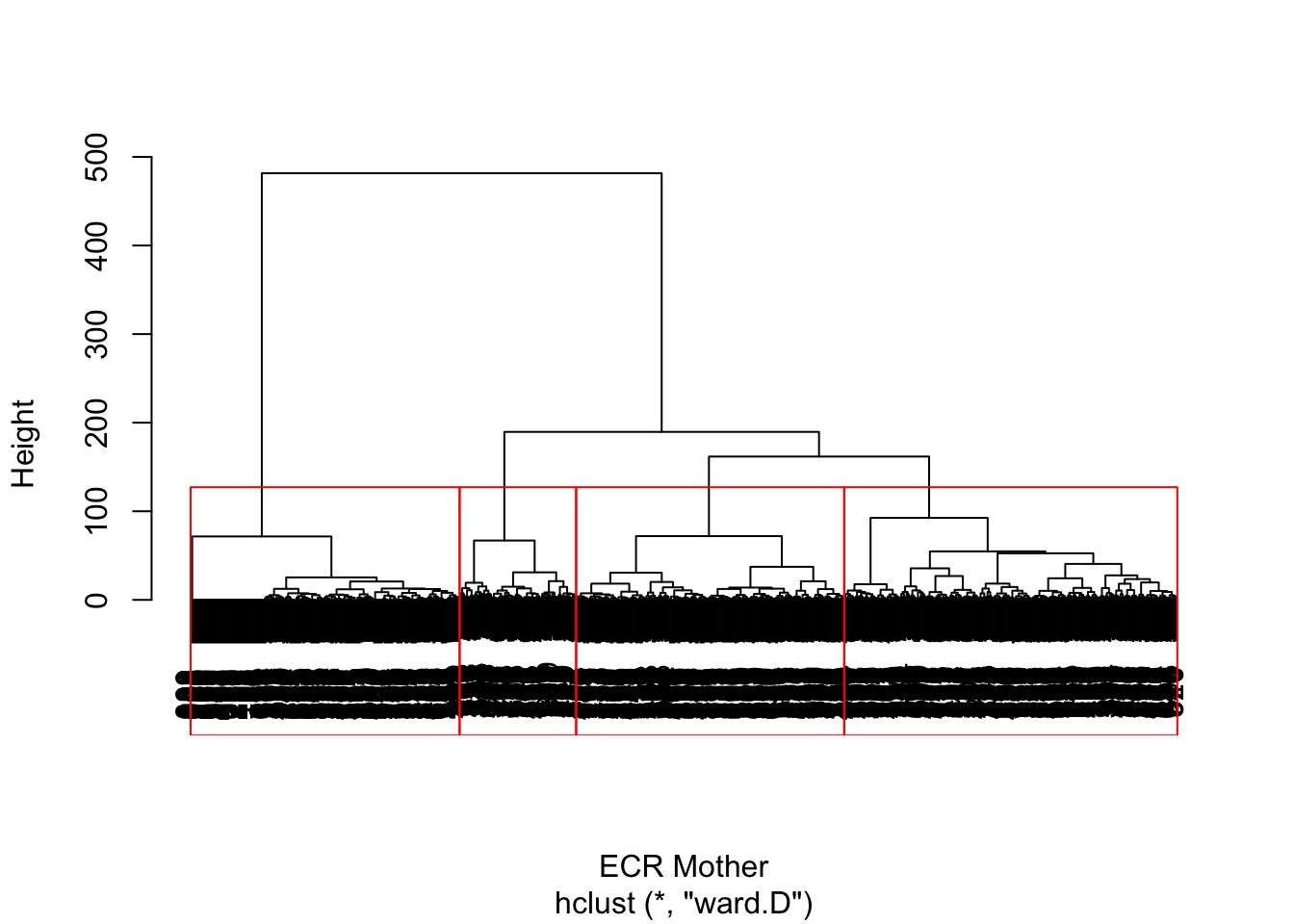

In Figure~1.3, Anxiety (“Anx”) and Avoidance (“Av”) scores are presented according to mother attachment styles. The frequencies of mother attachment styles according to gender are reported in Table~1.2.

Figure 1.3: Anxiety (“Anx”) and Avoidance (“Av”) scores according to mother attachment styles. Dashed lines represents overall average values (\(n_{subj} = 847\)).

| Gender | Secure | Anxious | Avoidant | Fearful |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 132 (16%) | 131 (15%) | 111 (13%) | 55 ( 6%) |

| Males | 99 (12%) | 155 (18%) | 119 (14%) | 45 ( 5%) |

| Total | 231 (27%) | 286 (34%) | 230 (27%) | 100 (12%) |

Compared to the overall average values of anxiety and avoidance, we can observe that:

- Secure children have lower levels of anxiety and avoidance

- Anxious children have higher levels of anxiety and about the average levels of avoidance

- Avoidant children have lower levels of anxiety and higher levels of avoidance

- Fearful children have higher levels of anxiety and avoidance

These results reflect the traditional definition of the four attachment styles.

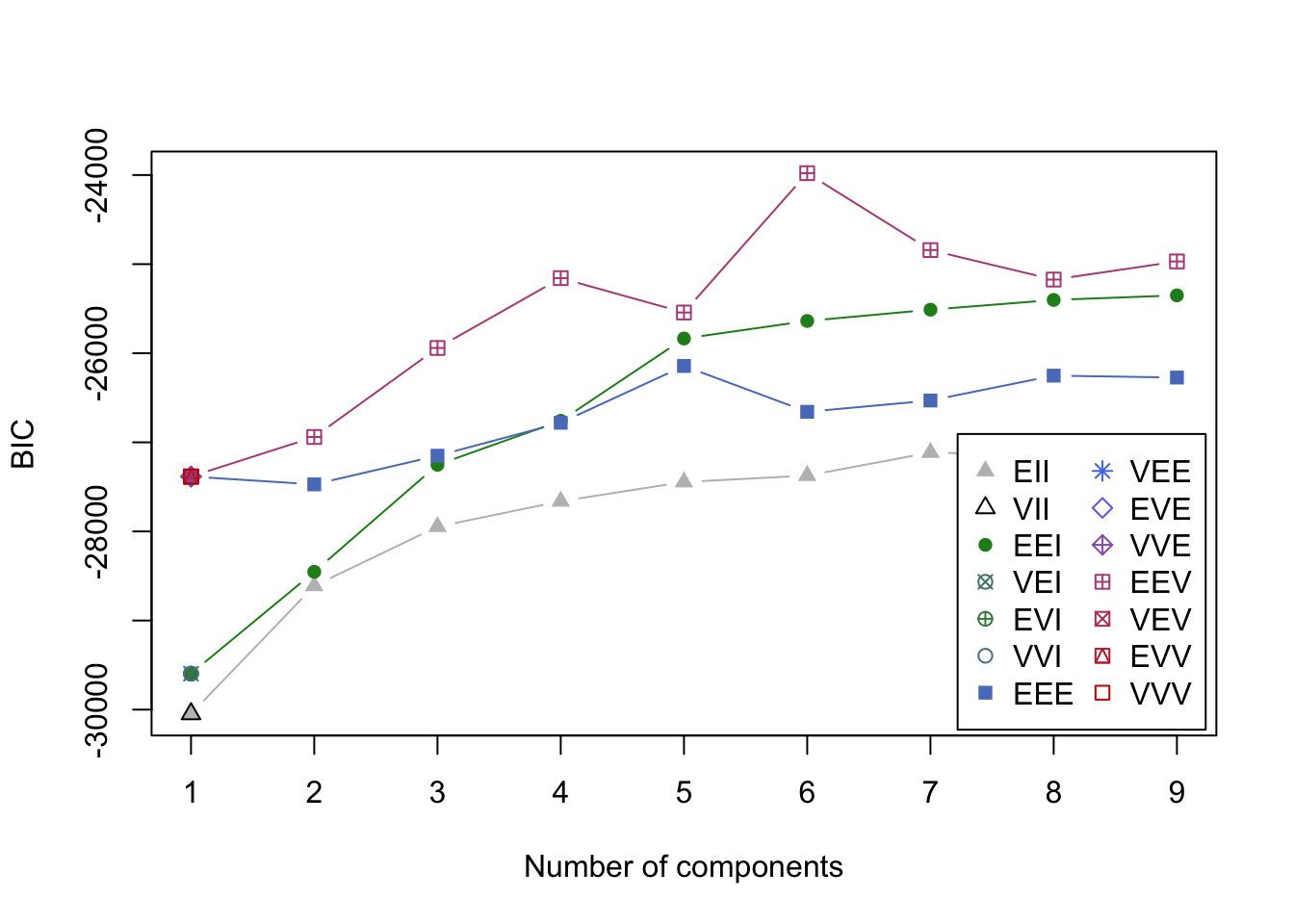

Mclust Check

To evaluate if 4 clusters is an appropriate choice, we compare the BIC values of different model-based clustering options. To do that we use the function mclustBIC() from the mclust R-package (Scrucca et al., 2016). BIC values of the best three model-based clusterings are reported below and overall results are presented in Figure~1.4. See ?mclustBIC() help page for further information.

## # Best model-based clustering for mother attachment

## Best BIC values:

## EEV,6 EEV,7 EEV,9

## BIC -23978.93 -24842.2954 -24969.9125

## BIC diff 0.00 -863.3681 -990.9852

Figure 1.4: BIC values of different model-based clustering options. See ‘?mclustBIC()’ help page for further information.

Results indicate the possible presence of a larger number of clusters. However, considering only 4 clusters seems to us the most reasonable choice. This is in line with attachment theory and general results in the literature. The important thing is that no smaller number of clusters provided better results than the division in 4 clusters.

1.3.2 Father Cluster Analysis

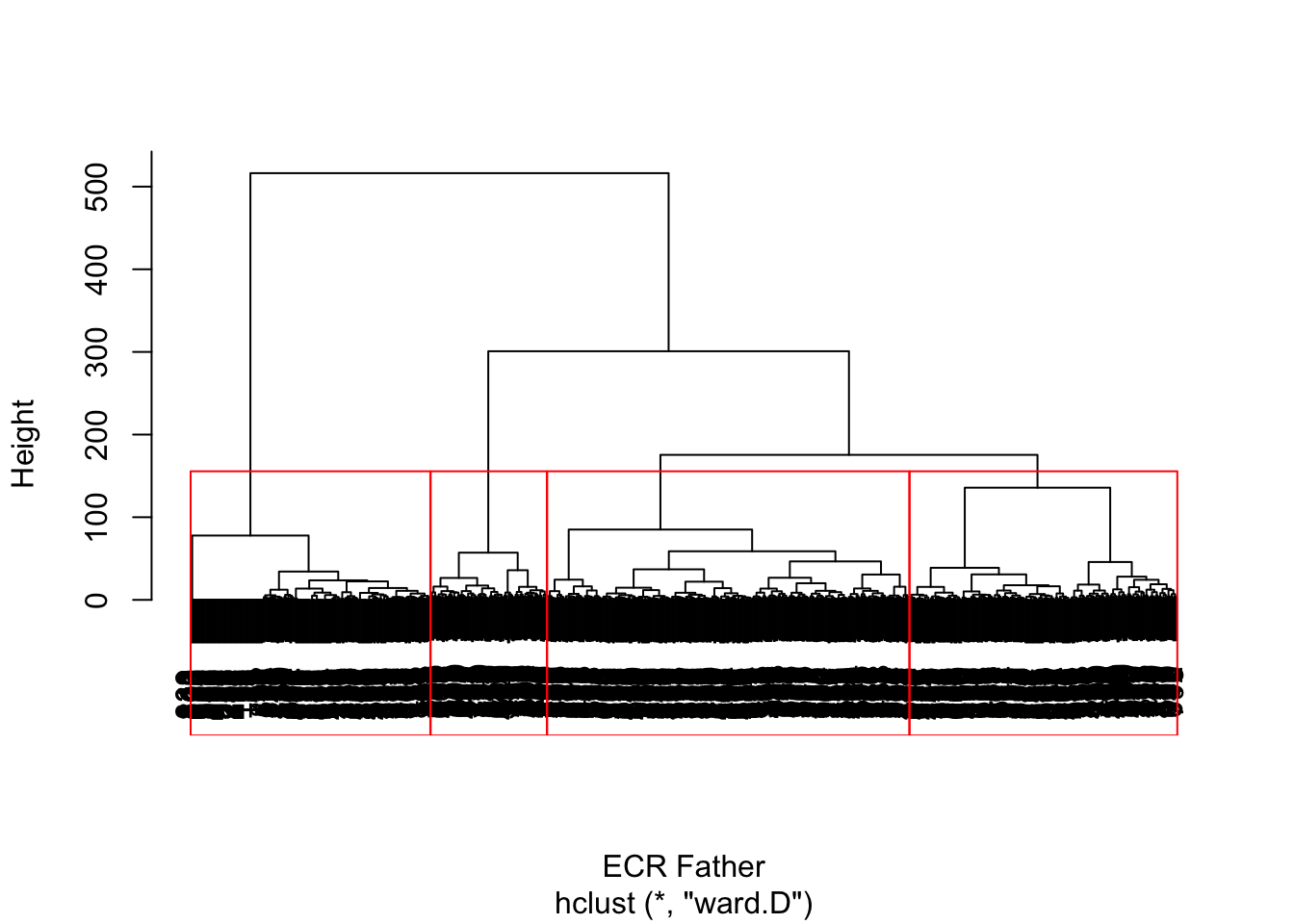

Regarding father attachment, 4 groups are selected from the cluster analysis results (see Figure~1.5).

Figure 1.5: Father attachment cluster dendrogram (\(n_{subj} = 847\)).

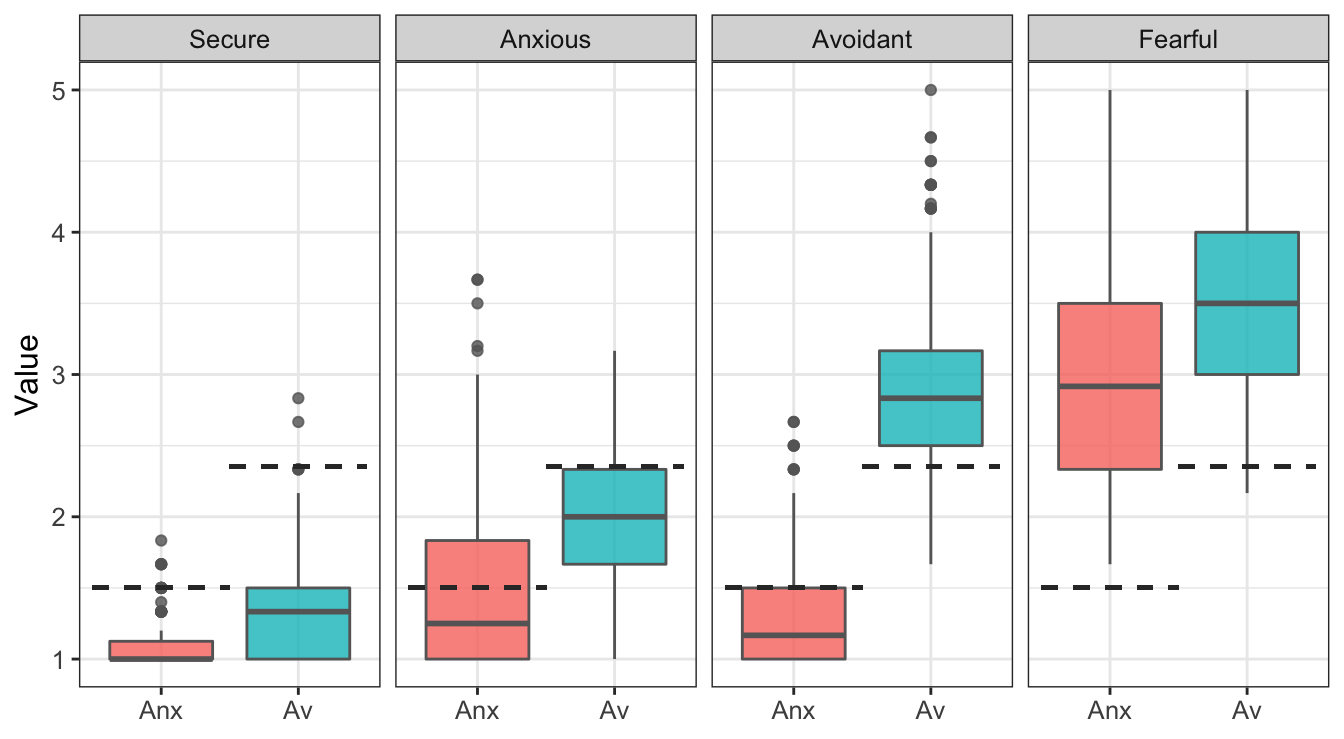

In Figure~1.6, Anxiety (“Anx”) and Avoidance (“Av”) scores are presented according to father attachment styles. The frequencies of father attachment styles according to gender are reported in Table~1.3.

Figure 1.6: Anxiety (“Anx”) and Avoidance (“Av”) scores according to father attachment styles. Dashed lines represents overall average values (\(n_{subj} = 847\)).

| Gender | Secure | Anxious | Avoidant | Fearful |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 99 (12%) | 104 (12%) | 163 (19%) | 63 ( 7%) |

| Males | 107 (13%) | 126 (15%) | 148 (17%) | 37 ( 4%) |

| Total | 206 (24%) | 230 (27%) | 311 (37%) | 100 (12%) |

Compared to the overall average values of anxiety and avoidance, we can observe that:

- Secure children have lower levels of anxiety and avoidance

- Anxious children have lower levels of anxiety and avoidance

- Avoidant children have lower levels of anxiety and higher levels of avoidance

- Fearful children have higher levels of anxiety and avoidance

These results are not as good as in the mother attachment classification, but they are still reasonable.

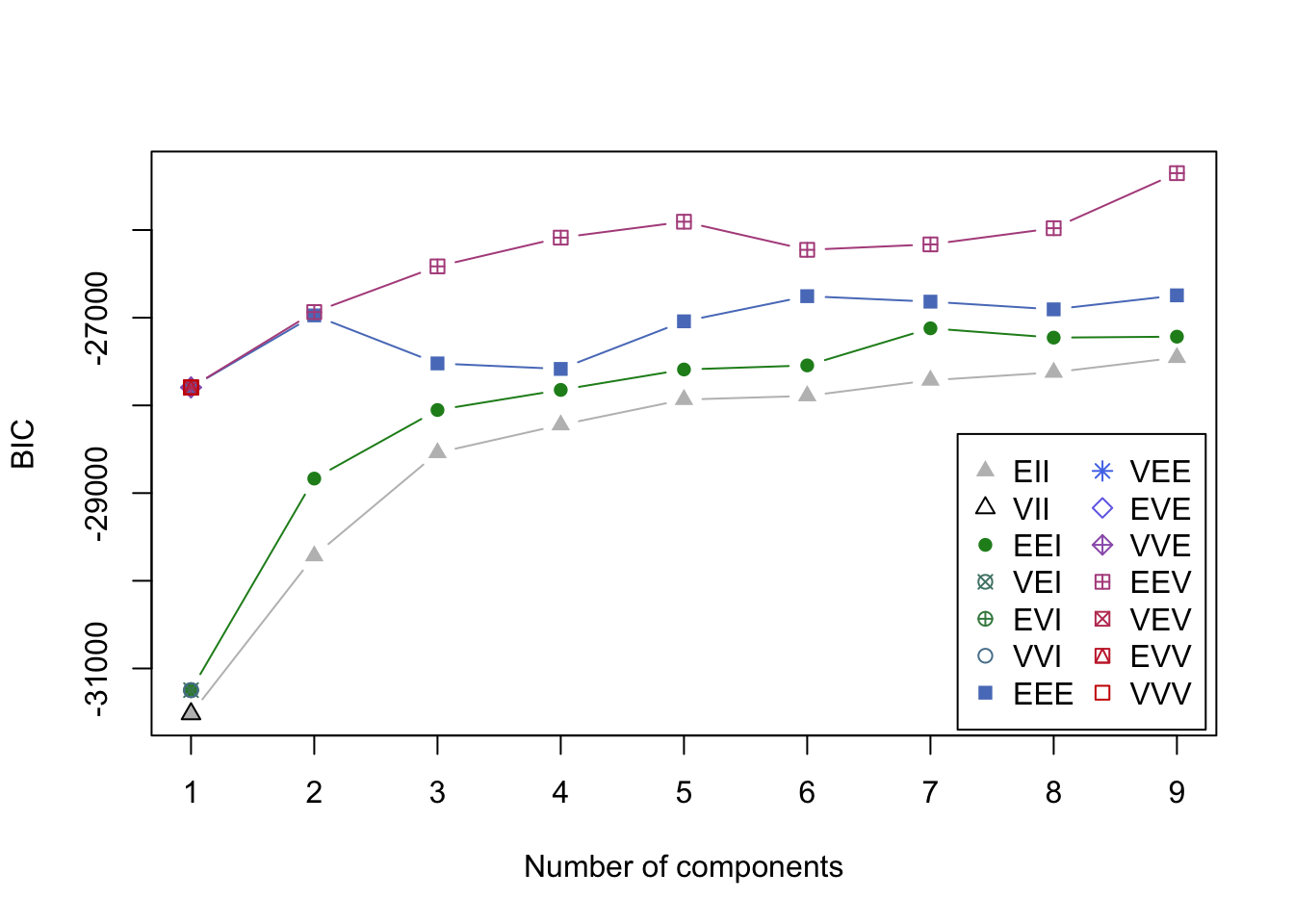

Mclust Check

To evaluate if 4 clusters is an appropriate choice, we compare the BIC values of different model-based clustering options as before. BIC values of the best three model-based clusterings are reported below and overall results are presented in Figure~1.7.

## # Best model-based clustering for father attachment

## Best BIC values:

## EEV,9 EEV,5 EEV,8

## BIC -25351.48 -25905.1973 -25979.1378

## BIC diff 0.00 -553.7208 -627.6613

Figure 1.7: BIC values of different model-based clustering options. See ‘?mclustBIC()’ help page for further information.

As for the mother, results indicate the possible presence of a larger number of clusters. However, considering only 4 clusters seems to us the most reasonable choice for the same reasons as before.

1.3.3 Mother and Father

The frequencies of mother attachment and father attachment styles are reported in Table~1.4.

| Mother Attachment | Secure | Anxious | Avoidant | Fearful |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | 125 (15%) | 49 ( 6%) | 49 ( 6%) | 8 (1%) |

| Anxious | 51 ( 6%) | 100 (12%) | 98 (12%) | 37 (4%) |

| Avoidant | 25 ( 3%) | 67 ( 8%) | 126 (15%) | 12 (1%) |

| Fearful | 5 ( 1%) | 14 ( 2%) | 38 ( 4%) | 43 (5%) |

We can observe how values on the diagonal (same attachment styles towards both parents) tend to be larger than others.

1.4 Children Outcomes

Children’s social-emotional development was measured using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, Goodman et al., 2010) completed by the teachers. Separate scores for externalizing and internalizing problems were obtained as the sum of the questionnaire items.

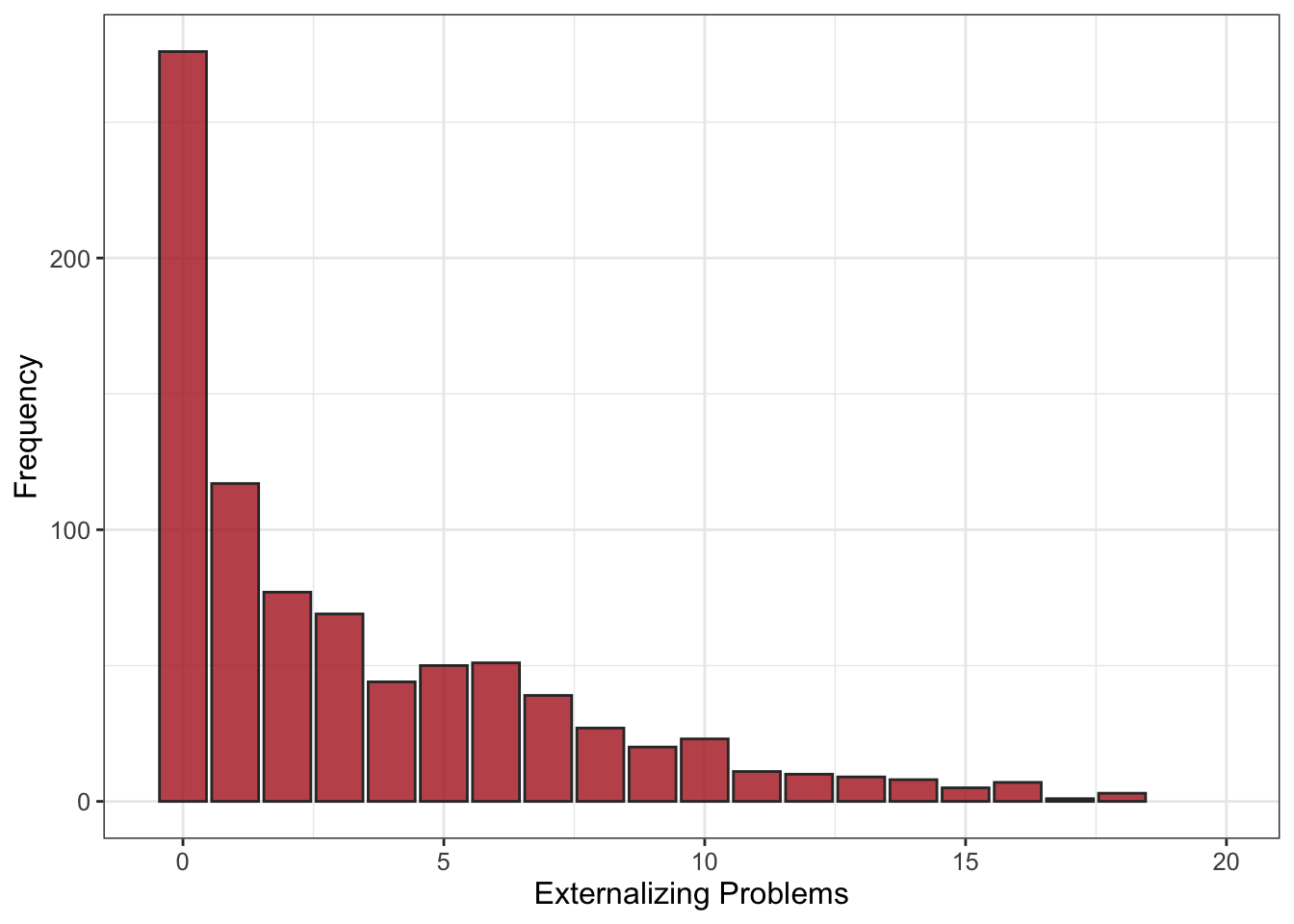

1.4.1 Externalizing Problems

Participants externalizing problems mean is 3.35 (SD = 3.91). The participants’ externalizing problems summary statistics are reported below and the distribution is presented in Figure~1.8.

## # Externalizing problems summary statistics

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.000 0.000 2.000 3.349 6.000 18.000

Figure 1.8: Participants externalizing problems distribution (\(n_{subj} = 847\))

Overall, externalizing problems are low. This is expected as the sample is not clinical. Externalizing problems according to attachment styles are reported in Table~1.5.

| Mother Attachment | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | 2.63 (3.57) | 1.0 | 3.45 (4.48) | 2.0 | 1.61 (2.13) | 1.0 | 2.88 (3.44) | 2.0 |

| Anxious | 3.69 (4.07) | 2.0 | 3.01 (3.61) | 2.0 | 3.32 (4.12) | 2.0 | 4.05 (3.61) | 3.0 |

| Avoidant | 2.84 (3.34) | 1.0 | 3.31 (3.65) | 2.0 | 3.71 (4.19) | 2.0 | 3.75 (4.81) | 1.0 |

| Fearful | 7.60 (4.04) | 8.0 | 4.64 (3.84) | 4.5 | 4.76 (4.67) | 3.0 | 4.26 (4.07) | 4.0 |

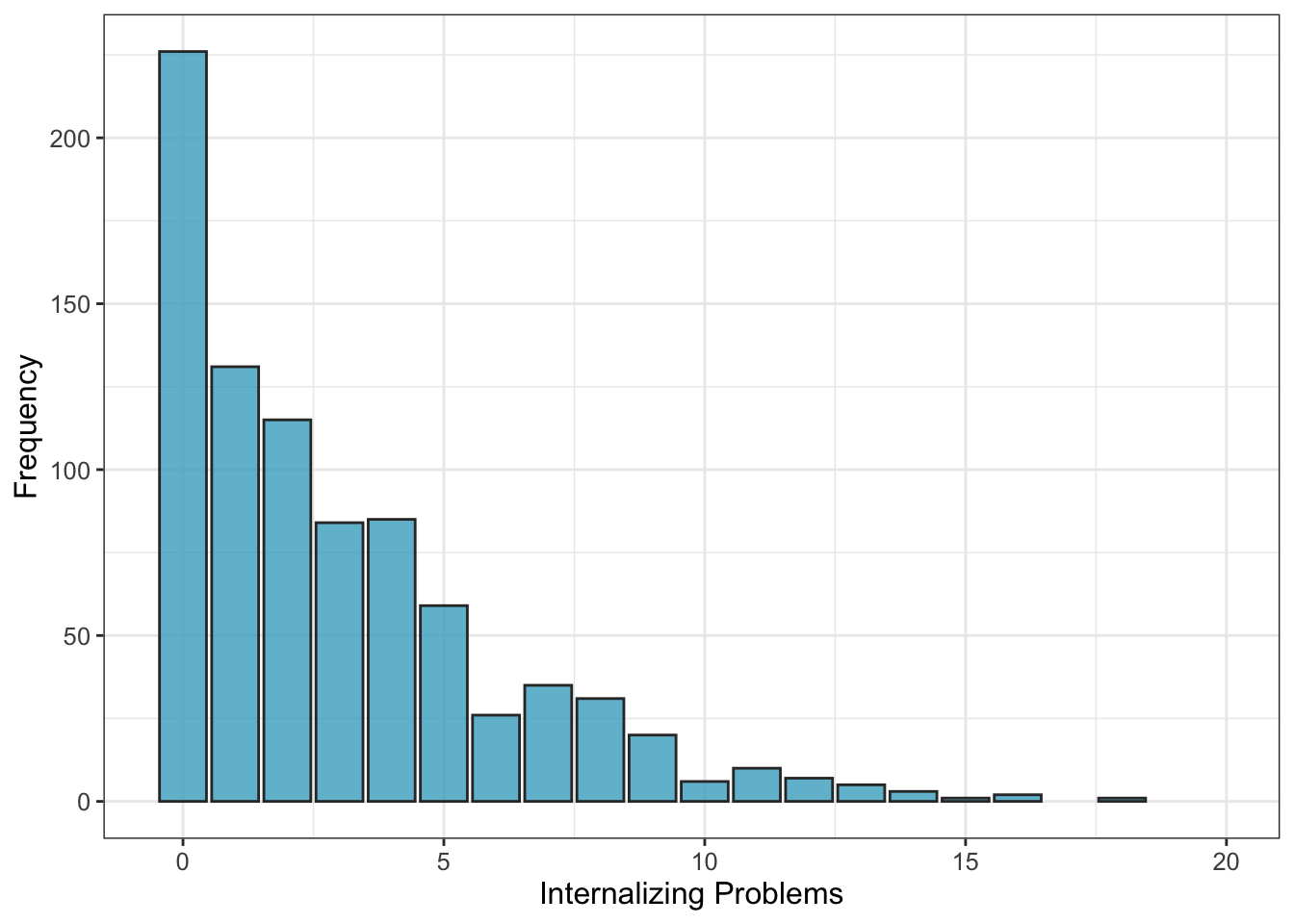

1.4.2 Internalizing Problems

Participants internalizing problems mean is 2.96 (SD = 3.14). The participants internalizing problems summary statistics are reported below and the distribution is presented in Figure~1.9.

## # Internalizing problems summary statistics

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.000 0.000 2.000 2.955 4.000 18.000

Figure 1.9: Participants internalizing problems distribution (\(n_{subj} = 847\))

Overall, internalizing problems are low. Again, this is expected as the sample is not clinical. Internalizing problems according to attachment styles are reported in Table~1.6.

| Mother Attachment | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | 2.29 (2.64) | 1.0 | 2.63 (2.75) | 2.0 | 2.67 (2.75) | 3.0 | 3.62 (3.46) | 3.0 |

| Anxious | 3.29 (3.48) | 2.0 | 3.15 (3.09) | 2.0 | 3.28 (3.72) | 2.0 | 3.11 (3.81) | 2.0 |

| Avoidant | 1.88 (2.28) | 1.0 | 2.99 (3.22) | 2.0 | 2.65 (2.86) | 2.0 | 4.08 (3.78) | 3.5 |

| Fearful | 4.40 (3.65) | 4.0 | 2.07 (1.69) | 2.0 | 3.68 (3.68) | 3.0 | 4.37 (3.12) | 4.0 |